These ultra-long experiments outlive their scientists — on purpose

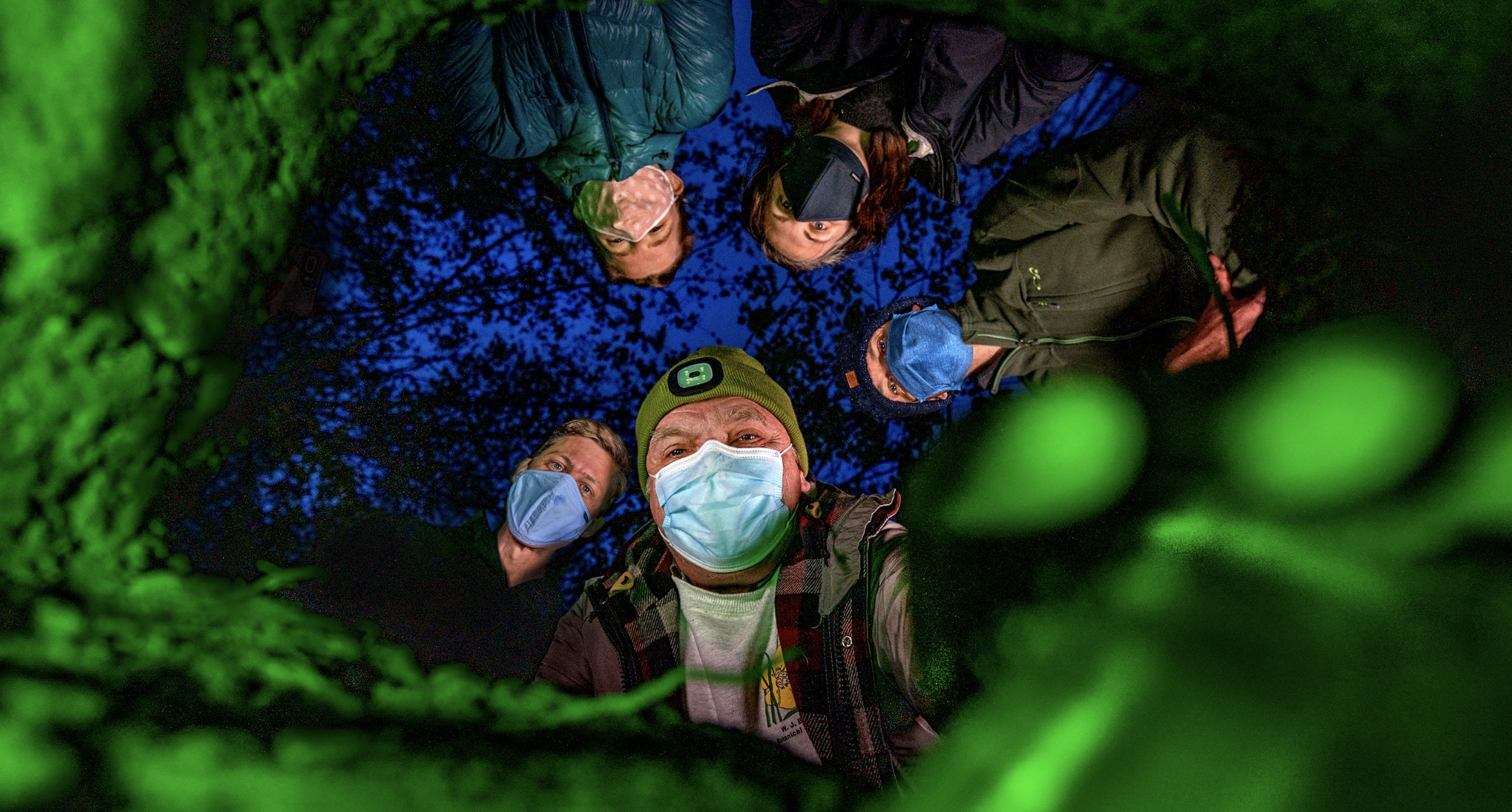

On a snowy night in 2021, four shivering scientists in Michigan set down their shovels and studied a hand-drawn map by flashlight. The map led to a secret location. They traveled in the dark so no one would spy where they were going.

If they dug in the right place, they expected to find a bunch of bottles made of thick glass. They’d been buried side-by-side almost 150 years earlier.

This was no ordinary hidden treasure. It was a science experiment. But not just a regular one of those, either.

In the fall of 1879, botanist William James Beal filled 20 pint-sized bottles with seeds and sand. Every bottle held 50 seeds each from 23 types of weeds. According to Beal’s journal, he had buried the bottles on a “sandy knoll” near the Michigan State University campus in East Lansing. He drew a map of this stash so he could unearth a bottle every five years.

He wanted to answer a simple question: How long can stored seeds still sprout? After all, seeds are alive but dormant. You can plant last year’s tomato seeds to get a new bounty this year.

But is there a cutoff? Do those dormant seeds eventually die or go bad?

That’s not a question you can answer quickly. The buried seeds certainly offer some useful clues. “Turns out,” says David Lowry, we now know those seeds can remain viable for “a long time.” Weed seeds, he says, can outlive the farmers who want them gone. “Some last decades, if not over a century.”

A plant biologist at Michigan State University, Lowry was there on that snowy night in 2021, wondering if they’d ever find Beal’s bottle. He’s among the latest in a long line of scientists who know where the bottles are buried. He’s also the current keeper of Beal’s map.

The lifespan of seeds isn’t the only thing that takes a lot of time and patience to measure. And the Beal seed inspectors aren’t the only scientists in it for the long haul. Long-term experiments have yielded surprising discoveries in biology, ecology, physics and space.

Read the full story by Stephen Ornes in Science News Explores.