Scribner on team to bring lake sturgeons back to Michigan's waters

Lake sturgeon are the oldest living fish species in the Great Lakes, first appearing in the fossil record about 135 million years ago. These fish are sentinels for the health of a river, and to the Anishinaabe and Menominee native American communities, lake sturgeon carry great spiritual significance. For two decades, the Black River Sturgeon Stream Side Research Facility in Onaway, Michigan, in partnership with Michigan State University and the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, has been dedicated to restoring this threatened species.

In 1997, the population of lake sturgeon in Black Lake in northern lower Michigan had decreased by 66%, and researchers estimated 566 adult lake sturgeon remained. This triggered a statewide effort to restore lake sturgeon to the lake that has continued for 20 years. Today 1,189 lake sturgeon call Black Lake home.

“This is one of the largest populations of lake sturgeon in the state,” says EEB core faculty member Kim Scribner, a professor in the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife in the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources. “We are committed to restoring the lake sturgeon population and understanding why sturgeon populations like this one are not self-sustaining.”

At the Black River Research Facility’s hatchery, lake sturgeon are bred and raised naturally through the egg, larvae and juvenile stages, then released back into the river.

Being located adjacent to the Black River means that the larvae produced in the river and raised in the hatchery are anthropogenically isolated, meaning there is limited immigration and emigration of sturgeon fish from other locations. A lake sturgeon fish could spend its entire life — up to 100 years — in the Black Lake system.

“We can do research that few others can,” Larson says. “The fish produced in the hatchery are representative of the successes and failures of natural spawning pairings in the wild.”

The 20 years of research also provides a long-term data set that is missing from most restoration research studies.

“The technology we use to study lake sturgeon has increased tremendously in several different areas,”

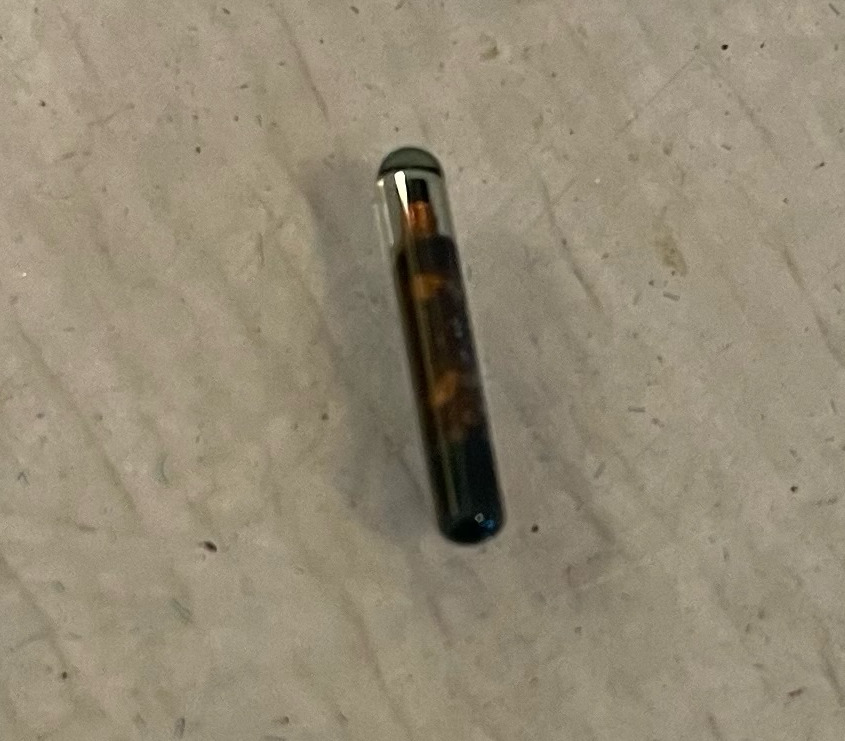

Scribner says. “How we track fish with tags is similar to what you’d put in your pet.”

Almost all of the 1,189 lake sturgeon in the Black River have been tagged with a passive integrated transponder, or PIT tag, inserted into the fish. PIT tags allow researchers to track individual fish and record biological information such as the fish’s weight, length, location and date of spawning. Researchers can also track their movement within the Black River system without a researcher ever having to touch the fish. Antennae arrays at the mouth of the Black River and along the riverbanks pick up the signals emitted from the PIT tags and record them.

MSU has been a leader in using DNA technology to look at the diets of lake sturgeon predators.

"We want to know if the predators are eating sturgeon or other things like insects because there isn’t enough sturgeon?” Scribner says. “We also monitor conditions like if there is a new moon with lots of light that can impact the number of sturgeons eaten. This has helped us gain tremendous insight into sturgeon predators.”

Researchers at the Black River facility are internationally known for their genetics research where they can look at the genetic makeup of the lake sturgeon that successfully spawned — at least once every three to four years — compared to fish that haven’t spawned. Thanks to the PIT tag technology, the researchers know which males most likely fertilized the females’ eggs. This means they can analyze the genetic data of the parents before lake sturgeon larvae grow into juveniles.

Like humans, sturgeon need time to grow up before they become parents. It takes male lake sturgeon approximately 15 years and females about 25 years before they are mature enough to spawn, which provides a large gap of time where the fish are vulnerable to predators and poachers.

Read the full story in MSU Today