Revealing 'evolution's solutions' to aging

An international team of 114 scientists has performed the most comprehensive study of aging and longevity to date with data collected in the wild from 107 populations of 77 species of reptiles and amphibians worldwide.

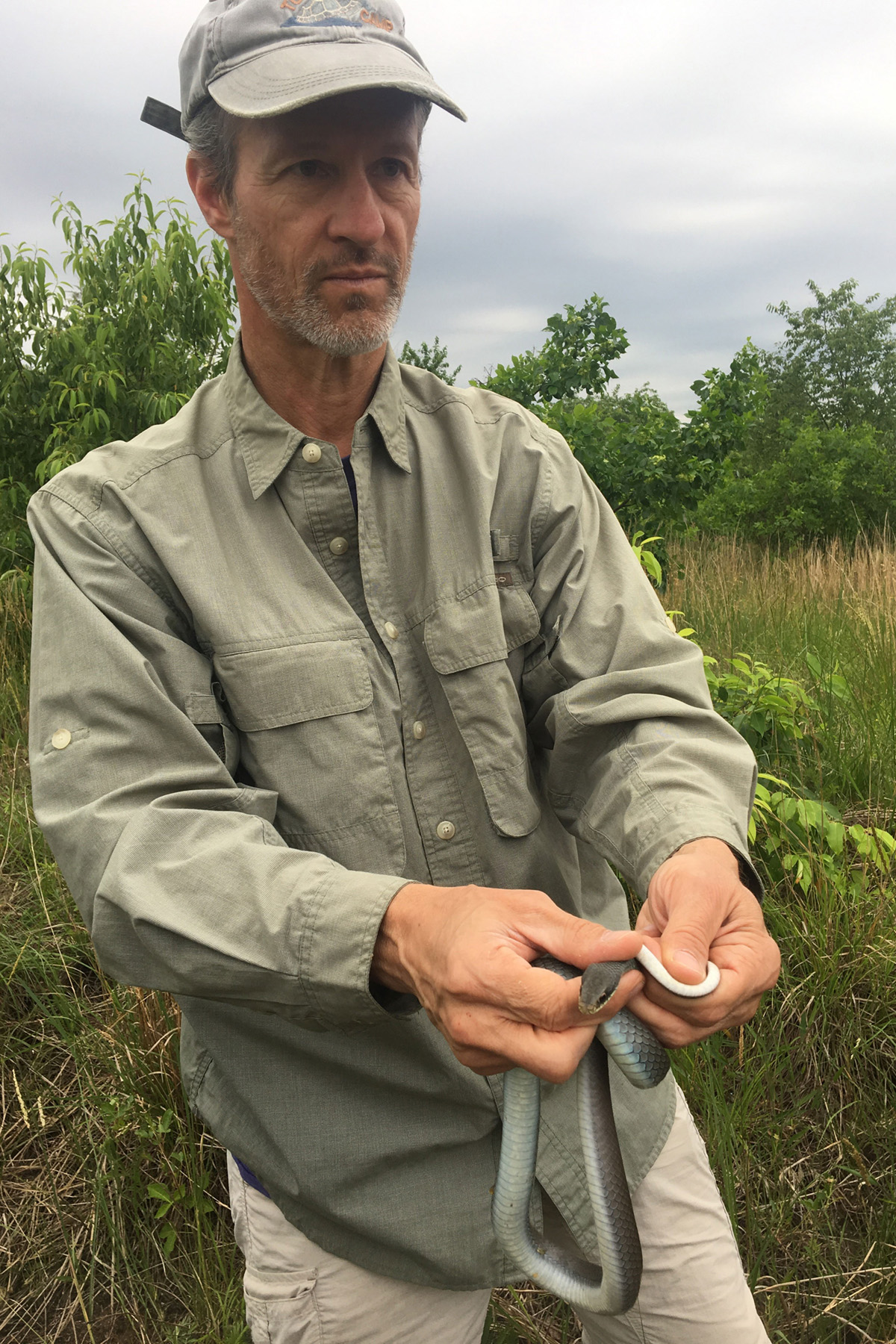

The team, led by researchers at Michigan State University, including EEB core faculty member Fredric Janzen, director of the W. K. Kellogg Biological Station (KBS) as well as a professor in the College of Natural Science and the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources. Co-leaders were from Pennsylvania State University and Northeastern Illinois University. Findings were reported in the journal Science on June 23.

Among their many findings, the researchers documented for the first time that turtles, salamanders and crocodilians (an order that includes crocodiles, alligators and caimans) have particularly slow aging rates and extended lifespans for their sizes.

“We are committed to studying long-lived species in the wild because nature has already done the experiment of ‘how to age slowly’,” wrote MSU researchers Anne Bronikowski and Fredric Janzen.

Bronikowski is one of the leaders of the study who recently joined MSU as a professor of integrative biology in the College of Natural Science and at KBS.

“Anne sometimes calls these examples ‘evolution’s solutions’ to growing old,” Janzen said.

“They are relevant to studies of human frailty because our cellular and genomic pathways are shared across much of animal life,” Bronikowski said.

In their study, the researchers applied methods used in both ecological and evolutionary sciences to analyze variation in aging and longevity of reptiles and amphibians. These “cold-blooded" or ectothermic animals offer a contrast to "warm-blooded" or endothermic mammals and birds.

“One of the interesting findings was that each group has a slow or negligible aging species across all these different ectotherms,” wrote Bronikowski and Janzen.

“It sounds dramatic to say that they don’t age at all,” said Beth Reinke, the first author of the Science report and an assistant professor of biology at Northeastern Illinois University. “But basically their likelihood of dying does not change with age once they’re past reproduction.”

Read the full story in MSU Today.