Changing fitness effects in long-term evolution experiment

The latest issue of Science magazine has a long-format research article on the bacterial populations in an

experiment started in 1988 by EEB core faculty member Richard Lenski.

With a team of researchers from Spain, France, and Harvard, Lenski and colleagues used high-throughput genomic methods to analyze the fitness effects of hundreds of thousands of mutations in the E. coli bacteria, and how those effects changed over time as the experiment proceeded.

Latest conclusion: Evolution is predictable.

See an interview with collaborator Spanish biologist Alejandro Couce story in the Spanish newspaper El País.

“You might think that evolution would run out of steam after 50,000 generations in a simple, constant environment,” Lenski said. “But we’ve shown previously (*Wiser et al., Science, 2013) that it doesn’t. In this paper, we shed light on how evolution is so endlessly creative, even in a static world—as beneficial changes occur, they open up new opportunities for exploration and improvement.”

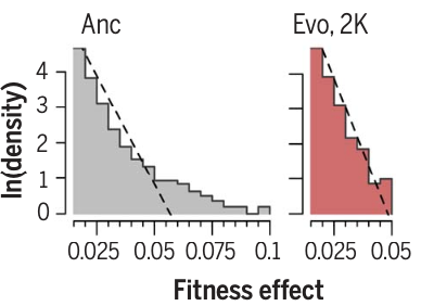

They found that the long tail of beneficial mutations became shorter over time, and

that the identity of the genes that harbor potential beneficial mutations also changed.

Moreover, the identity of essential genes—those required for the cells to survive

and reproduce—changed over time, often in repeatable ways across the independently

evolving lineages.

They found that the long tail of beneficial mutations became shorter over time, and

that the identity of the genes that harbor potential beneficial mutations also changed.

Moreover, the identity of essential genes—those required for the cells to survive

and reproduce—changed over time, often in repeatable ways across the independently

evolving lineages.

You can read the paper in Science: Changing fitness effects of mutations through long-term bacterial evolution

Also, Lenski tells a backstory to the paper that “sheds light on how civility, cooperation, and collaboration can succeed even in the highly competitive world of science” in An Update to the Changing Distribution of Fitness Effects.

“Like many of the papers about the long-term evolution experiment, this was a collaboration with scientists from other universities and around the world,” Lenski said. “And it required a very unusual and special kind of collaboration because the paper actually represents a fusion of what started as two separate papers—what could have become a tense competition instead became a fun cooperation.”